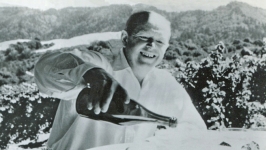

Jesse Ziff Cool : The Good-for-You Food Trailblazer

Jesse Ziff Cool's inspired credo of “ingredients first” comes full circle. This rule-breaking chef, educator and nationally recognized restaurateur of Flea Street Café continues to make organic, clean ingredients her tastemaking superstars.

She has owned five restaurants, written seven books—including one entirely about toast—penned numerous magazine articles, written a regular food column for the local newspaper, appeared on TV, taught classes at Stanford and led cooking classes at Draeger’s. For more than 40 years, as a chef, educator and restaurateur, Jesse Ziff Cool has led the charge in the good-for-you local food movement and championed efforts for sustainable agriculture to eco-conscious food service, locally and around the country.

A self-professed hippie chick, as a tastemaker and organic food champion Jesse Ziff Cool is most widely known for Flea Street Café, which opened in Menlo Park in 1980 serving organic, sustainable, ingredient-driven food. Long before sourcing chemical-free, local ingredients was mainstream and sought out by dining customers and cooks, her restaurant delighted diners and her positive advocacy for the “good food” movement was felt in California cuisine, and beyond. Her first restaurant, Late for the Train opening in 1976, was considered by celebrated cookbook author Joyce Goldstein to be one of the first, if not the very first restaurant in the nation to source only organic ingredients.

Her book Simply Organic is one part cookbook, one part autobiography and one part treatise on the Jesse Ziff Cool food philosophy. It begins with the simple phrase, “You are what you eat.”

It sounds so simple, but it was revolutionary when she began as a devotee of ingredients that are local, fresh, in-season and free of chemicals. Jesse learned it all from her family, growing up outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She helped tend the family garden, raise chickens and watched the regular deliveries of compost. Her dad owned a grocery store stocked with organic fruits and vegetables and a German-style bakery where everything was made from scratch. He churned milk into custard and made ice cream with locally grown strawberries and peaches. An avid observer, Jesse watched her dad wait those extra few days to pick till the fruit looked past-its-prime, but was deliciously sweet.

“It’s not about ‘organic,’” she says. “It’s about not poisoning people.” She wrote a piece for a local paper about a woman she met in a supermarket, proud that she was serving her child fresh strawberries. “Do you realize your strawberries are soaked in methyl bromide?” she wrote. “The strawberry association almost got me fired.”

For Jesse, it is always been about the farmers. From the “No Farms, No Food” bumper sticker on her car to the reverence with which she holds the profession, there is probably no bigger advocate.

“If you have a good potato, a little salt and pepper and maybe some butter will make it taste delicious. I want to taste the food and not be confused.”

Jesse doesn’t call herself a chef. “I don’t like the word.” She prefers “food political activist” or, slightly tongue in cheek, “cooker person.”

Her philosophy and restaurants are all about clean food. No pesticides or chemicals, no fillers or enhancers, no preservatives. “I’m so old-fashioned. Keep it simple and highlight the delicious ingredients.”

She’s had her differences with her chefs over the years. They always want to do more and Jesse wants them to do less. “Just let it be the way it is.” Mostly, they work it out. “It takes a lot for me to pull the owner card.”

Fringes create change

As someone who spent most of her life on the food fringe, Jesse admits the fight has not been easy.

The vocabulary you would use today to describe her cuisine in the 1970s—farm-to-table, sustainable, California cuisine—had not yet been associated with food or restaurants. The word “organic” was not promoted on the menu, as with the phrase came expectations of limited and flavorless, raw cuisine.

And in the early days, it was hard to find organic ingredients. She would regularly send vendors and suppliers away because they could not say how the products were grown, harvested or prepared for sale.

Gradually, she built her supply chain. She was a regular at the Palo Alto Farmers' Market when it first opened 30 some years ago. “I had to sneak in with my ’67 Chevy truck before they opened because it was illegal for farmers to sell wholesale.” She found kindred spirits with Bill Niman of Niman Ranch, one of the first local beef and meat suppliers who did not use hormones.

It’s gotten better. She cultivated a group of “keepers of the gate,” brokers who share her passion for clean food, grown, raised and prepared for sale in humane ways. She found farm-raised seafood suppliers on the Pacific Coast that have been delivering great seafood. “I trust them and they trust me. And we pay good money for it.”

Our Provence

For a foodie like Jesse, there is no place like home. If you are going to insist on clean, no-chemicals foods, you can’t be shipping them across the country. She considers the Bay Area “our Provence, because everything grows here.” Prior to becoming the tech capital of Silicon Valley, Santa Clara Valley was known as the Valley of Heart’s Delight for its fertile soil and year-round temperate climate.

Local vintners have been taking advantage. “The Santa Cruz AVA is going to be the next great wine region because of the soil and climate and the grapes that are grown responsibly and ethically.” Jesse has had Santa Cruz wines on the restaurant menu since the beginning. And is now offering diners a Winemaker Dinner Series, featuring notable winemakers like Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon Vineyard.

If these walls could talk

Jesse has stories to tell about the local luminaries who have enjoyed her cooking. She is happy to host them, but goes out of her way to treat them just like every other diner. “Do you want me to kick someone out?” she once asked a very famous caller with an even more famous presidential guest when the restaurant was full. They get a table just like everyone else she says, and everyone seems to like it best that way.

She’s had Steve Jobs dining with Bill Gates and catered Chelsea Clinton’s graduation party at Stanford. Sergey Brin and Larry Page talked Google with Al Gore. Mark Zuckerberg met Sheryl Sandberg there to discuss her joining Facebook. Jesse actually cooked an entire dinner with Zuck (they were neighbors at the time). Sheryl even brought Oprah in one night.

How was it with Oprah? “She made me want to go shoe shopping.” Huh? “She had on these red shoes with four-inch heels. They had flames coming out the back.”

While she enjoys entertaining like this, she doesn’t flaunt it. “The only pictures I have at Flea Street are of my parents.”

What’s next

How does it feel to know that everything you were talking about back then is now mainstream food culture?

“We were way ahead of our time. We thought we were going to change the world. We believed we were right, but there was no proof to back up what we were saying about clean, chemical-free food.” And years later? “We were right. I’m just glad to have lived to see it.”

She is happier now than she’s been in a long time. “This is the best staff I’ve had in years.” Jesse continues to looks for ways to find chefs, staff and servers that truly believe in the promise of crafting and serving bold, flavorful, and clean food tied to seasonal, local ingredients, each and every day.

Jesse just signed a 10-year lease for Flea Street so they will continue to serve it up as only she can do, and reimagine good food for all. The restaurant was one of the first in the area to sign a pledge more than a year ago to become a Sanctuary Restaurant. The Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC) designation supports immigrants and refugees, as well as people of all genders, faiths, races, abilities and sexual orientations.

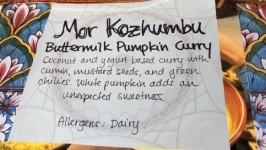

Hospital food is her next project. “We all end up there.” She is working with Stanford and Sodexo, a hospital food service supplier, to reshape food in hospitals. Some of it is easy—she had them rearrange the placement of the food at the cafeteria food line so the vegetables and grains were first, followed by the proteins, and people ate smaller portions of proteins. Other things are harder. There are 120 diets in a typical hospital.

Flea Street has been around for almost four decades, driven by Jesse’s vision of how to eat. “I have learned that I need to be true to my philosophy.”

After all, you are what you eat.

Living Like a Local: Behind the Scenes with Jesse Ziff Cool

• Jesse’s beloved copy of The Joy of Cooking, purchased in the early 1970s served as her muse for reimagining recipes with new ingredient combinations, and certainly reflects her joyous approach to food.

![]() • Still the hippie chick, she keeps a colorful blue/purple streak of hair tucked behind her ear.

• Still the hippie chick, she keeps a colorful blue/purple streak of hair tucked behind her ear.

• She employs a “garden fairy” Tiffany who tends the restaurant garden, and Jesse is one of the first chefs to grow and serve from her own seasonal produce and eggs.

• Many luminaries have dined at Flea Street, “everyone except Barack Obama,” she says wistfully.

• One regret is not using the backstage passes to see Willy Nelson at FarmAid. She stayed home to cover when her restaurant manager quit.

![]() • She’s embarking on a series of workshops with farmer families in Pescadero, sharing recipes and techniques using just seven common ingredients.

• She’s embarking on a series of workshops with farmer families in Pescadero, sharing recipes and techniques using just seven common ingredients.

• Jesse also runs the Cool Café at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford. Come for the Rodin, but stay for fresh eats.